Case Report

Diagnosis and Treatment of Anterior Cracked Tooth: A Case Report

Wellington Luiz de Oliveira Da Rosa1, Lucas Pradebon Brondani1, Tiago Machado Da Silva2, Evandro Piva3 and Adriana Fernandes Da Silva3*

1DDS, Post-graduate Student, Faculty of Dentistry, Federal University of Pelotas, RS, Brazil

2Undergraduate Student, Faculty of Dentistry, Federal University of Pelotas, RS, Brazil

3DDS, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Federal University of Pelotas, Pelotas, RS, Brazil

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Adriana Fernandes da Silva, Department of Restorative Dentistry, Federal University of Pelotas, Gonçalves Chaves St., 457, room 504, Zip Code: 96015-560, Pelotas, RS, Brazil, Tel: +55 53 32256741 (134); Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 21 January 2017; Approved: 23 February 2017 ; Published: 24 February 2017

How to cite this article: Da Rosa WLO, Brondani LP, Silva TM, Piva E, Silva AF. Diagnosis and Treatment of Anterior Cracked Tooth: A Case Report. J Clin Adv Dent. 2017; 1: 012-020. DOI: 10.29328/journal.jcad.1001003

Copyright License: © 2017 Da Rosa WLO, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Cracked tooth; Dental curing light; Dental restoration repair; Case report

Abstract

Background: A cracked tooth may be challenging for dentists because it may present with varied intensities, may be asymptomatic, and may still not be clinically visible. The transilumination method can facilitate diagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment in such cases. The aim of the present article was to report a clinical case of an anterior cracked tooth with a nonesthetic class IV restoration.

Clinical considerations: A 22-year-old male patient with chief complaint of esthetics of upper front tooth reported a history of dental trauma. Transilumination with a dental curing light unit was used to examine the region. The tooth 11 was diagnosed with several cracks and a nonesthetic class IV restoration. For repair, the universal adhesive system Scotchbond Universal was applied without previous acid etching, followed by the application of Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for body) above the old restoration, taking care to slightly overlap the fracture line with the composite and to not extend the composite until the incisal margin. Subsequently, a thin layer of Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for enamel) was applied over the bevel until the incisal margin, and the tooth shape was carved.

Conclusion: This case report demonstrates simplified diagnosis of an anterior cracked tooth with transilumination; following repair, the esthetic quality of the restoration was considered satisfactory and approved by the patient.

INTRODUCTION

A cracked tooth may be described as a tooth with crack lines of varying intensities [1]. Several terms and classifications have been proposed to explain different conditions of cracked teeth [2,3]. The American Association of Endodontists (AAE) [4] divides cracks into 5 types: craze lines, fractured cusp, cracked tooth, split tooth, and vertical root fracture. Owing to this variety of intensity, diagnosing a tooth crack as well as determining the appropriate treatment can be extremely challenging [5,6]. In certain cases, the cracks cannot be easily visualized, and the symptoms can vary depending on the direction and rate of progression of the cracks [5,6].

Cracks in natural teeth must be considered as a clinical concern because it presents at a reported frequency of 4%-5% in every 100 adults, with molars representing over 75% of cases [7]. The causative factors of a tooth crack may vary, but masticatory function is the most common factor related to vertical tooth fracture in posterior teeth [8]. In addition, trauma may be a factor to be considered, primarily in anterior teeth. Besides, cracked teeth may cause sharp pain upon biting, present unexplained cold sensitivity, pain on release of pressure, or deep-probing depths associated with the crack [8-10]. Nevertheless, crack lines occurring at an early stage may not be visible and may also not present any pain or reaction to cold and hot stimuli [11,12].

Therefore, biomechanical and periodontal prognoses as well as treatment requirements of a cracked tooth depend on what aspects of the tooth are intersected by the existing partial fracture of the stress plane [13]. Thus, several techniques are available for management of cracked teeth, ranging from continuous monitoring, direct restoration, and the replacement of fractured teeth by dental implants and ceramic crowns [14]. The present study aimed to report a clinical case of an anterior cracked tooth that presented in a nonesthetic class IV restoration.

CASE REPORT

This study is reported according to The CARE guidelines [15]. A 22-year-old Caucasian male reported to the clinic at the Faculty of Dentistry with chief complaints regarding esthetics.

Diagnosis and etiology

The patient had reported trauma in the same region 10 years back, being hit by a stone thrown while playing: one tooth was lost, whereas the other had fractured. The patient’s past medical history did not reveal any significant finding. He was otherwise systemically healthy and was not on any medications. Moreover, he had no history of smoking and alcohol or any other deleterious habits.

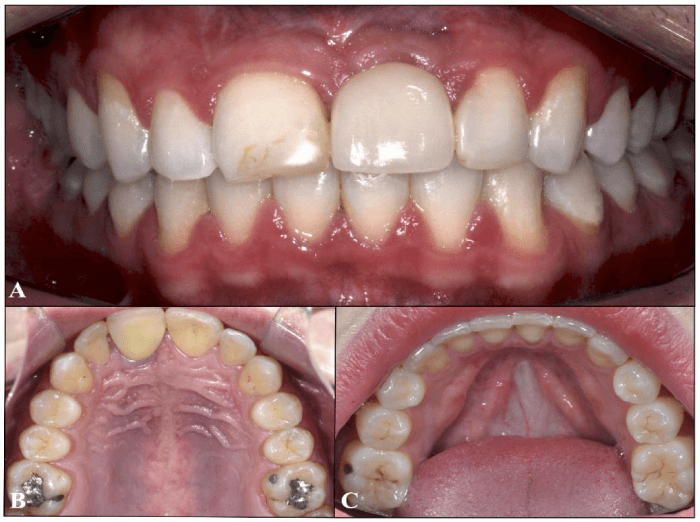

On examination, there was a dental implant with a ceramic crown on the left maxillary lateral incisor (21) and amalgam restorations on the right maxillary first molar (16) (occlusal and lingual), left maxillary first molar (26) (occlusal and lingual), and left mandibular first molar (36) (buccal). A class IV composite resin restoration involving both incisal corners present on the right maxillary central incisor (11) was the tooth with the primary complaint (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Examination of patient: (A) Frontal view showing a ceramic crown on the left maxillary lateral incisor (21) and a class IV composite resin restoration on the right maxillary central incisor (11) that was the chief complaint of patient; (B) amalgam restorations on the right maxillary first molar (16) (occlusal and lingual) and the left maxillary first molar (26) (occlusal and lingual); (C) amalgam restoration on the left mandibular first molar (36) (buccal).

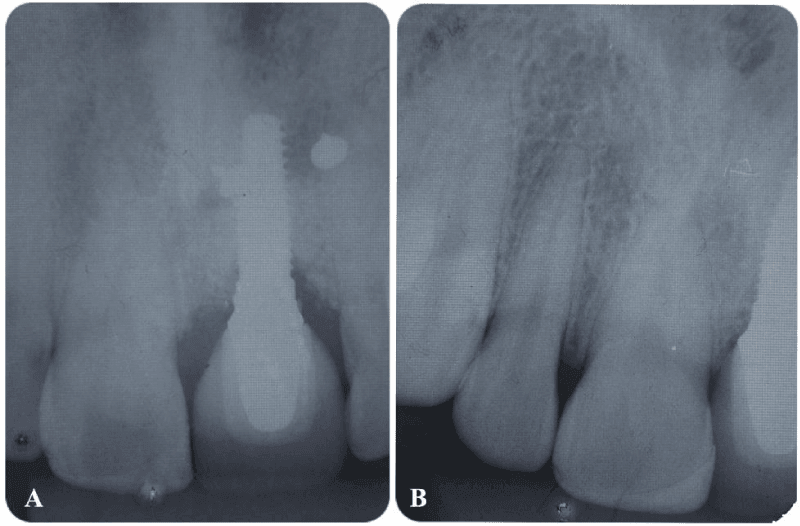

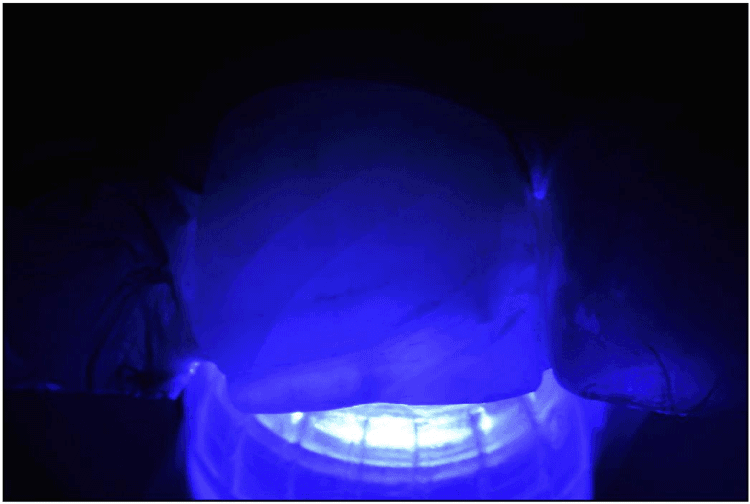

Initially, pulp vitality tests revealed that the central incisor (11) was vital. Radiographs recorded as part of the examination included the anterior maxillary region that showed no signs of periapical pathologies (Figure 2). Subsequently, dental curing light (Radii Cal; SDI, Bayswater, Victoria Australia) was used as a transilluminator, being placed on the lingual surface of 11 to evaluate the presence of cracks; this allowed visualization of horizontal cracks in the tooth (Figure 3). Hard and soft tissue examination revealed no underlying hard or soft tissue pathologies.

Figure 2: Radiographical examination with no signs of periapical pathologies: (A) maxillary anterior periapical radiograph and (B) maxillary anterior view with Clark’s positioning.

Figure 3: Transilumination with the dental curing light unit (Radii Cal; SDI, Bayswater, Victoria Australia) placed on the lingual surface of right maxillary central incisor (11), which allowed visualization of horizontal cracks in the tooth.

Following examination and diagnosis, because the lingual portion of the restoration was appropriately adapted, the selected treatment plan was to remove the buccal portion of the esthetic restoration, followed by repair of the vestibular surface with a composite resin.

Treatment objectives

Moreover, the patient’s chief complaint was with regard to the esthetic restoration. Mimicking the natural characteristics of teeth can be challenging, and achieving good esthetics is usually the main purpose of restorative dental treatments [16]. The final quality of the restoration may depend on various factors, including appropriate selection of materials and shades [16-18]. Besides, the placement of an enamel bevel may be a good choice to improve esthetics, and previous studies have shown that this can result in better adhesion [19], better esthetics [20], and reduced marginal microleakage [21,22]. Although a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that enamel beveling does not improve retention rate or avoid marginal discoloration of cervical composite restorations [23], we prepared an enamel bevel in order to hide the transition between the tooth and the restorative material [20,24].

Treatment objectives

In order to achieve better esthetics, a combination of different color shades of distinct opacity was used to mimic the natural appearance of teeth. In addition, the restoration was repaired to simplify the procedure, maintaining the lingual surface of the old composite, thus ensuring appropriate adaptation. Among advantages of repair, simpler restorations may be time saving and may enhance moisture control [25,26]. Moreover, the repair of composites have been reported to provide favorable outcomes in terms of longevity and quality of the restoration [16,18,25-27].

Treatment options

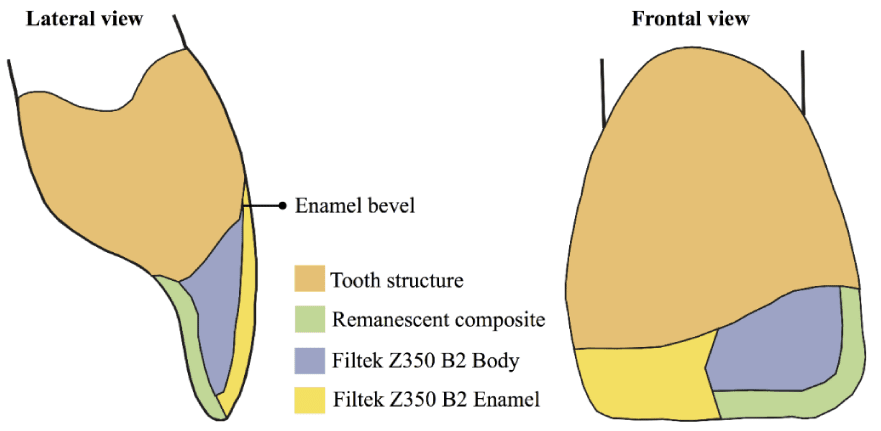

For repair treatment, the composite resin shade was accurately selected with the help of a Vita scale (VITA Zahnfabrik, Sackingen, Germany) (Figure 4) and through direct color selection with the insertion and light curing of small increments of resin on the tooth enamel. Since the adjacent incisor was a ceramic crown that did not present a translucent incisal edge, the selected color type for the nanofilled composite Filtek Z350 (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was B2 for body and B2 for enamel (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA). The color maps planned to be used are represented in figure 5. After removal of the buccal portion of previous restoration with a diamond bur (1014, KG Sorensen, Cotia, Brazil), the surface of the remaining composite was left slightly roughened with a diamond bur to facilitate adhesion. Subsequently, a 2-mm bevel was placed in a cavosurface margin by using a flame-shaped diamond bur (Figure 6).

Figure 4: Color of the composite resin selected with the help of the Vita scale (VITA Zahnfabrik, Sackingen, Germany).

Figure 5: Color maps show layers of composite resin planned to be used in the restoration. The frontal view shows a cutaway portion and the surface layer.

Figure 6: Tooth after removal of the buccal portion of previous restoration with a diamond bur and a 2-mm bevel placed in the cavosurface margin with a flame-shaped diamond bur.

After color selection, isolation was achieved using a rubber dam (Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil) to prevent substrate contamination (Figure 7A). Adjacent teeth (21 and 12) were protected, and the universal adhesive system Scotchbond Universal (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was applied and light cured (Radii Cal; SDI, Bayswater, Victoria Australia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions without previous acid etching (Figure 7B).

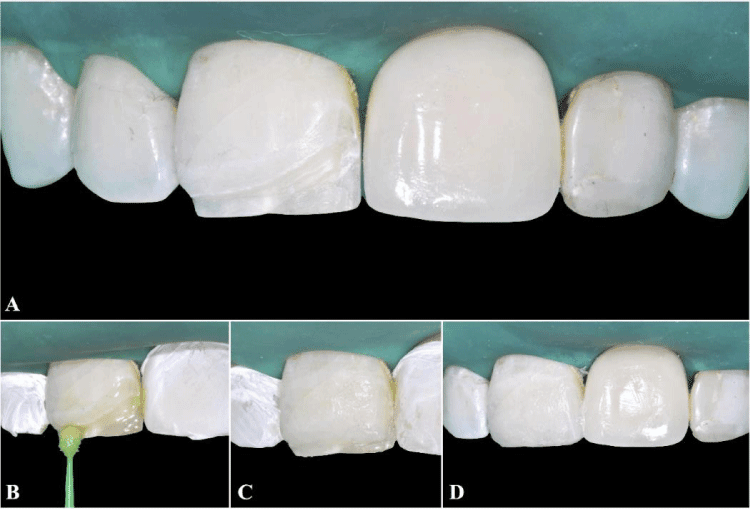

For repair, the nanofilled composite Filtek Z350 (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was applied using incremental and stratified techniques with 2-mm-thick increments to reconstruct lost tooth faces. Initially, Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for body) was applied over the old existing restoration (Figure 7C), taking care to slightly overlap the fracture line with the composite and to not extend this composite until the incisal margin. The composite increments were light cured (Radii Cal; SDI, Bayswater, Victoria Australia). Then, a thin layer of Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for enamel) was applied over the bevel until the incisal margin, the tooth shape was carved, and the composite was light cured (Figure 7D).

Figure 7: Repair procedure: (A) isolation performed with a rubber dam (Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil) to prevent substrate contamination of maxillary anterior teeth (13, 12, 11, 21, 22, and 23); (B) the universal adhesive system Scotchbond Universal (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) was applied and light cured (Radii Cal; SDI, Bayswater, Victoria Australia); (C) Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for body) applied above the old restoration and light cured; (D) Filtek Z350 of color type B2 (for enamel) applied over the bevel until the incisal margin. The tooth shape was carved and the composite resin was light cured.

Figure 8: Final aspect of restoration after finishing and polishing the restoration with multilaminate tips, Soft-lex discs Pop-on (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA), and Ultradent silicone cups (Utah, USA).

An occlusal test was performed using carbon paper. During the same appointment, finishing and polishing of the restoration was achieved using multilaminate tips, Soft-lex discs Pop-on (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA), and Ultradent silicone cups (Utah, USA). Moreover, enamel perikymata were reproduced by drawing small transverse ridges on the tooth surface with the help of a diamond bur (2135FF, KG Sorensen, Cotia, Brazil). Subsequently, the restorations were polished using a felt disc and diamond paste (Diamond Flex, FGM, Joinville, Brazil) from the direction of the composite resin toward the tooth.

TREATMENT RESULTS

The esthetic quality of the restoration was considered satisfactory by the patient. Figure 8 presents the final aspect of the restoration that was also approved (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Patient’s smile after restoration. The esthetic quality of the restoration was considered satisfactory and approved by the patient.

DISCUSSION

Cracked teeth have been a diagnostic challenge owing to the challenge of locating the crack lines of incomplete fracture [2,28]. Although the most common cracked teeth are molars [29], anterior teeth may also be affected as the case reported [7,1]. Coronal fractures of permanent teeth are very common in young individuals, primarily in the incisal third of the central anterior teeth [30,31]. Our case presented a previously restored fracture and “craze lines” adjacent to the fracture that were asymptomatic. In such cases, treatment requires continuous monitoring and restoration [32]. The clinical symptoms vary according to the position and extent of the crack s, and most clinicians may not find the presence of a crack if the fracture plane is <18-µm wide [11,28]. According to a previous study, most common methods to diagnose a cracked tooth include naked eyes (48%), transillumination (18%), dye staining (17%), microscopic examination (9%), and diagnostic surgery (8%) [28]. The transillumination method can reveal whether or not there is a crack [33,34], and we used this method with a dental curing light unit owing to its convenience and ease of use.

Regarding the adhesive, we used a universal adhesive with the versatility of being adaptable to the clinical situation and that can be applied by self-etching or etching and rinsing [35]. In our case, the universal adhesive was applied using self-etching, which is easy to use, has a faster application procedure, and is less susceptible to differences in the operator’s technique compared with the multistep etch-and-rinse adhesives [35-37]. Moreover, it can reduce the risk of postoperative sensitivity [35,38,39]. However, a recent meta-analysis of in vitro studies showed that prior acid etching of mild universal adhesives improves the bond strength to enamel but not to dentin [35]. Additional clinical studies are warranted to evaluate the long-term efficacy of such adhesives.

Furthermore, compared with other composite resins, nanofilled composites have been reported to demonstrate the smoothest surfaces after polishing and brushing with less color change [40,41]. However, a recent review reported that there is no in vitro evidence to support the selection of nanocomposites over microhybrids based on better surface smoothness and/or gloss [42]. Regardless of the material used, most failures in anterior teeth are attributed to esthetic reasons [16]. Various factors influence the appearance of a restoration: so far, accurate shade matching and successful simulation of the anatomical shape are the major concerns for obtaining an esthetic restoration [30]. In addition, the nanocomposite material used and the polishing direction used are vital factors for obtaining an optimally polished and smooth surface, which, in turn, contributes to the esthetic results obtained as well as patient satisfaction [43].

A careful diagnosis, appropriate case treatment, and continuous monitoring are fundamental to que accurate management of cracked teeth. Taken together, the present case report demonstrated simplified diagnosis of an anterior cracked tooth with transilumination, followed by the repair of an esthetic restoration. The esthetic quality of the restoration was considered satisfactory and approved by the patient.

REFERENCES

- Kang SH, Kim BS, Kim Y. Cracked Teeth: Distribution, Characteristics, and Survival after Root Canal Treatment. J Endod. 2016; 42: 557-562. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Hwy33o

- Ellis SG. Incomplete tooth fracture--proposal for a new definition. Br Dent J. 2001; vol: 190: 424-428. Ref.: https://goo.gl/k4z2uh

- Ritchey B, Mendenhall R, Orban B. Pulpitis resulting from incomplete tooth fracture. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957; 10: 665-670. Ref.: https://goo.gl/WOiVWh

- Endodontists A Ao. Cracking the cracked tooth code. Endodontics: Colleagues for Excellence. 2008; Chicago: American Association of Endodontists.

- Capar ID, Uysal B, Ok E, Arslan H. Effect of the size of the apical enlargement with rotary instruments, single-cone filling, post space preparation with drills, fiber post removal, and root canal filling removal on apical crack initiation and propagation. J Endod. 2015; 41: 253-256. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1ODpb3

- Liu HH, Sidhu SK. Cracked teeth--treatment rationale and case management: case reports. Quintessence Int. 1995. 26: 485-492. Ref.: https://goo.gl/z6ujeb

- Bader JD, Martin JA, Shugars DA. Preliminary estimates of the incidence and consequences of tooth fracture. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995; 126: 1650-1654. Ref.: https://goo.gl/sqlv1F

- Krell KV, Rivera EM. A six year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulpitis: treatment and prognosis. J Endod. 2007; 33: 1405-1407. Ref.: https://goo.gl/a1fR1O

- Banerji S, Mehta SB, Millar BJ. Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 1: aetiology and diagnosis. Br Dent J. 2010; 208: 459-463. Ref.: https://goo.gl/qY27og

- Homewood CI. Cracked tooth syndrome--incidence, clinical findings and treatment. Aust Dent J. 1998; 43: 217-222. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UBgJtb

- Cameron CE. The cracked tooth syndrome: additional findings. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976; 93: 971-975. Ref.: https://goo.gl/yniG4n

- Turp JC, Gobetti JP. The cracked tooth syndrome: an elusive diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996; 127: 1502-1507. Ref.: https://goo.gl/oFLmkE

- Mamoun JS, Napoletano D. Cracked tooth diagnosis and treatment: An alternative paradigm. Eur J Dent. 2015; 9: 293-303. Ref.: https://goo.gl/WBnele

- Lubisich EB, Hilton TJ, Ferracane J. Northwest Precedent. Cracked teeth: a review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2010; 22: 158-167. Ref.: https://goo.gl/QfY9oj

- Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, et al. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. J Med Case Rep. 2013; 7: 223. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Swb8kx

- Baldissera RA, Correa MB, Schuch HS, Collares K, Nascimento GG, et al. Are there universal restorative composites for anterior and posterior teeth? J Dent. 2013, 41: 1027-1035. Ref.: https://goo.gl/BV7OPJ

- Demarco FF, Correa M , Cenci MS, Moraes RR, Opdam NJ, et al. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: not only a matter of materials. Dent Mater. 2012; 28: 87-101. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LwbKTT

- Opdam NJ, van de Sande FH, Bronkhorst E, Cenci MS, Bottenberg P, et al. Longevity of posterior composite restorations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent Res. 2014; 93: 943-949. Ref.: https://goo.gl/pgTHWN

- Ikeda T, Uno S, Tanaka T, Kawakami S, Komatsu H, et al. Relation of enamel prism orientation to microtensile bond strength. Am J Dent. 2002; 15: 109-113. Ref.: https://goo.gl/kX2kpT

- Baratieri LN, Ritter AV. Critical appraisal. To bevel or not in anterior composites. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2005; 17: 264-269. Ref.: https://goo.gl/FlELgY

- Mazhari F, Mehrabkhani M, Sadeghi S, Malekabadi KS. Effect of bevelling on marginal microleakage of buccal-surface fissure sealants in permanent teeth. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009; 10: 241-243. Ref.: https://goo.gl/H9PDib

- Swanson TK, Feigal RJ, Tantbirojn D, Hodges JS. Effect of adhesive systems and bevel on enamel margin integrity in primary and permanent teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2008; 30: 134-140. Ref.: https://goo.gl/1cNZOw

- Schroeder M, Reis A, Luque-Martinez I, Loguercio AD, Masterson D, et al. Effect of enamel bevel on retention of cervical composite resin restorations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015; 43: 777-788. Ref.: https://goo.gl/YWlQeF

- Donly KJ, Browning R. Class IV preparation design for microfilled and macrofilled composite resin. Pediatr Dent. 1992; 14; 34-36. Ref.: https://goo.gl/f3rDr6

- Mjor IA, Gordan VV. Failure, repair, refurbishing and longevity of restorations. Oper Dent. 2002; 27: 528-534. Ref.: https://goo.gl/0lPTVs

- Staxrud F, Dahl JE. Role of bonding agents in the repair of composite resin restorations. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011; 119: 316-322. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Hn4sKe

- Gordan VV, Shen C, Riley J 3rd, Mjör IA. Two-Year Clinical Evaluation of Repair versus Replacement of Composite Restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006; 18: 144-154. Ref.: https://goo.gl/M5Ofq3

- Imai K, Shimada Y, Sadr A, Sumi Y, Tagami J. Noninvasive cross-sectional visualization of enamel cracks by optical coherence tomography in vitro. J Endod. 2012; 38: 1269-1274. Ref.: https://goo.gl/8bT1I2

- Seo DG, Yi YA, Shin SJ, Park JW. Analysis of factors associated with cracked teeth. J Endod. 2012; 38: 288-292. Ref.: https://goo.gl/Uq0tCE

- Baratieri LN, Monteiro Junior S, Correa M, Ritter AV. Posterior resin composite restorations: a new technique. Quintessence Int. 1996; 27: 733-738. Ref.: https://goo.gl/UP7JEI

- Valente LL, Münchow EA, Peralta SL, de Souza NC : Conservative dentistry: non-beveled esthetic restorations in anterior teeth. Rev Gaúch Odontol. 2014; 62: 443-448. Ref.: https://goo.gl/FCwHP6

- Paul RA, Tamse A, Rosenberg E. Cracked and broken teeth--definitions, differential diagnosis and treatment. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim (1993). 2007; 24: 7-12. Ref.: https://goo.gl/53wY8J

- Jun MK, Ku HM, Kim E, Kim HE, Kwon HK, et al. Detection and Analysis of Enamel Cracks by Quantitative Light-induced Fluorescence Technology. J Endod. 2016; 42: 500-504. Ref.: https://goo.gl/n6V4QP

- Fried WA, Simon JC, Lucas S, Chan KH, Darling CL et al. Near-IR imaging of cracks in teeth. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2014; 18. Ref.: https://goo.gl/b9YTPd

- Rosa WL, Piva E, Silva AF. Bond strength of universal adhesives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015; 43: 765-776. Ref.: https://goo.gl/LnXdz1

- Luque-Martinez IV, Perdigão J, Muñoz MA, Sezinando A, Reis A, et al. Effects of solvent evaporation time on immediate adhesive properties of universal adhesives to dentin. Dent Mater. 2014; 30: 1126-1135. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jKb1zu

- Wagner A, Wendler M, Petschelt A, Belli R, Lohbauer U. Bonding performance of universal adhesives in different etching modes. J Dent. 2014; 42: 800-807. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jCxc5P

- Chen C, Niu LN, Xie H, Zhang ZY, Zhou LQ, et al. Bonding of universal adhesives to dentine--Old wine in new bottles? J Dent. 2015; 43: 525-536. Ref.: https://goo.gl/KRy7aH

- Perdigão J, Loguercio AD. Universal or Multi-mode Adhesives: Why and How? J Adhes Dent. 2014; 16: 193-194. Ref.: https://goo.gl/A5RKMU

- Reddy PS, Tejaswi KL, ShettyS, Annapoorna BM, Pujari SCm, et al. Effects of commonly consumed beverages on surface roughness and color stability of the nano, microhybrid and hybrid composite resins: an in vitro study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2013; 14: 718-723. Ref.: https://goo.gl/IgzQtK

- Senawongse P, Pongprueksa P. Surface roughness of nanofill and nanohybrid resin composites after polishing and brushing. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2007; 19: 265-273, discussion 74-75. Ref.: https://goo.gl/YfSOaU

- Kaizer MR, de Oliveira-Ogliari A, Cenci MS, Opdam NJ, Moraes RR. Do nanofill or submicron composites show improved smoothness and gloss? A systematic review of in vitro studies. Dent Mater. 2014; 30: 41-78. Ref.: https://goo.gl/ilHukt

- St-Pierre L, Bergeron C, Qian F, Hernández MM, Kolker JL, et al. Effect of Polishing Direction on the Marginal Adaptation of Composite Resin Restoration. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2013; 25: 125-138. Ref.: https://goo.gl/jYnx57